Agricultural Revolution: How Technology Transformed the American West

The agricultural transformation of the American west

The 1920s mark a pivotal era in American agriculture, peculiarly in the western states. Follow World War i, the agricultural landscape undergoes dramatic changes as new technologies, farming methods, and economic pressures converge to remake the region. This transformation affect not solely how farming was conduct but besides reshape western communities, economies, and environments.

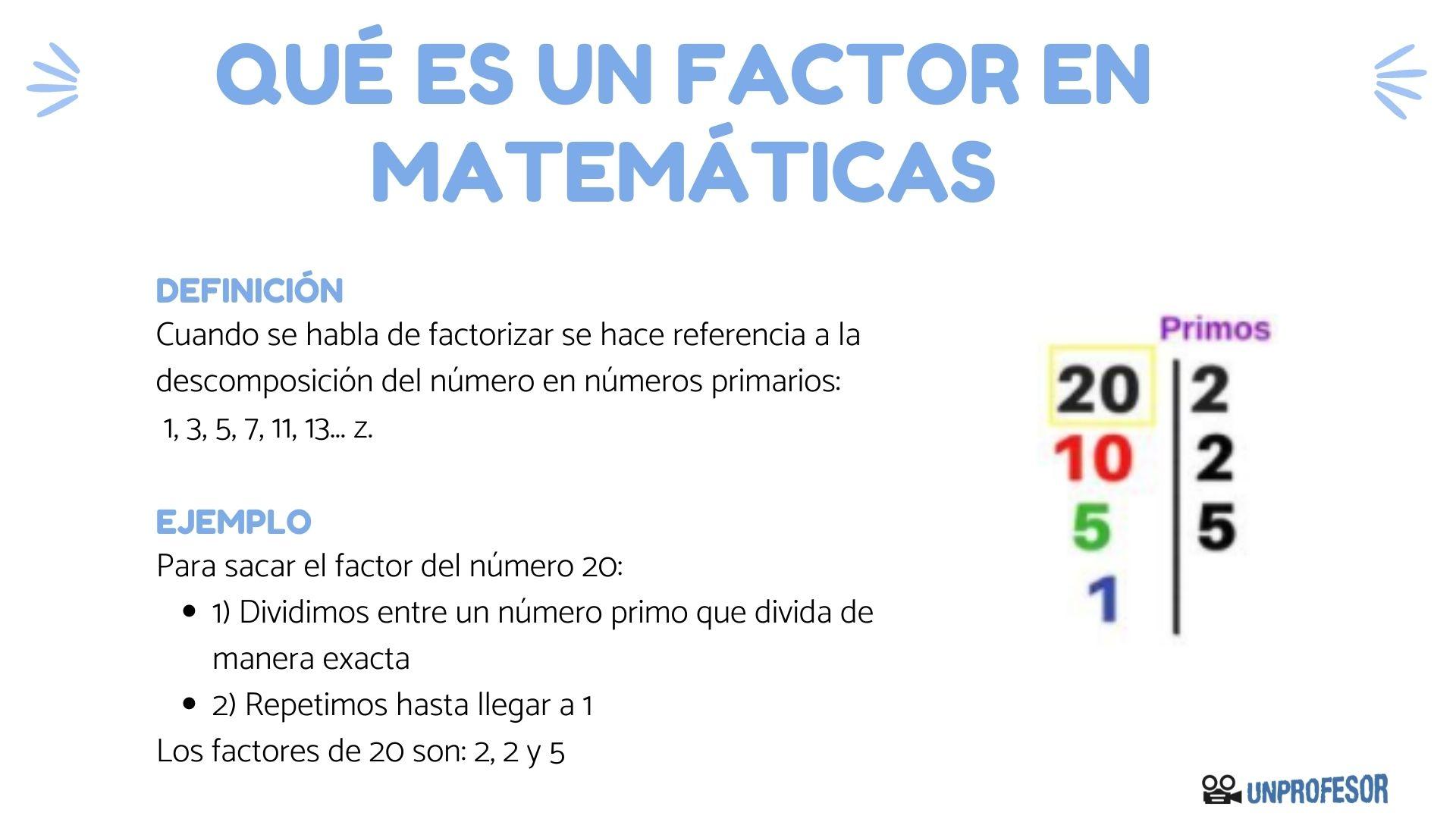

Mechanization revolution

Peradventure the virtually visible change in western agriculture during the 1920s was the rapid adoption of mechanical farming equipment. The tractor emerge as the symbol of this agricultural revolution, replace horse draw implements and essentially change farm operations.

The rise of the tractor

By 1920, roughly 246,000 tractors operate on American farms. Within a decade, that number explode to over 920,000. Western states lead this adoption trend, with California, Oregon, Washington, and the great plains states embrace mechanization at remarkable rates.

The ford son tractor, introduce in 1917 and mass produce throughout the 1920s, make mechanical farming accessible to average farmers. Price at roughly$7500 (compare to earlier models cost $$2000 $3,000 ))these machines represent both opportunity and financial risk for western farmers.

A single tractor could replace 5 7 horses, reduce the need for feed crops and free up land for market production. This mechanical efficiency allow farmers to cultivate larger acreages with less labor, essentially alter the economics of western agriculture.

Combines and specialized equipment

The combine harvester revolutionize grain production across the west. These machines, which combine reaping, threshing, and winnow operations, dramatically reduce harvest labor requirements. In wheat produce regions like eastern Washington, northern Oregon, and the Dakotas, combines cut harvest time by more than half while reduce labor costs by up to 60 %.

Specialized equipment for different crops proliferate throughout the decade. Mechanical cotton pickers transform labor patterns in Arizona and California’s cotton regions. Mechanical potato diggers, sugar beet harvesters, and fruit sort machines create new efficiencies for western specialty crop producers.

Irrigation expansion

Water management represent another technological frontier that reshape western agriculture during the 1920s. Federal reclamation projects, private irrigation companies, and individual farmers expand irrigation networks throughout the arid west.

Federal reclamation projects

The bureau of reclamation, establish in 1902, accelerate its dam building and irrigation projects during the 1920s. Key developments include:

- Completion of arrow rock dam inIdahoo( 1915) and subsequent canal expansion through the 1920s

- Development of the salt river project in Arizona

- Expansion of the Yakima project in Washington

- Plan for the boulder canyon project (late hHoover Dam)

These massive infrastructure projects transform millions of acres of arid land into productive farmland. The salt river project solely brings irrigation to over 200,000 acres in centralArizonaa, enable the cultivation of cotton, citrus, and vegetable crops inantecedenty unproductive desert lands.

Groundwater development

Improvements in pump technology allow western farmers to tap groundwater resources at unprecedented rates. Electric and gasoline power pumps replace windmills and manual systems, enable deeper wells and more reliable water supplies.

In California’s central valley, groundwater development explode during the 1920s. The number of irrigation wells in the San Joaquin valley increase from roughly 1,500 in 1920 to over 6,000 by 1930. This water access transforms the valley into one of the world’s virtually productive agricultural regions.

Irrigation technology advances

Beyond water delivery systems, innovations in application technology improve irrigation efficiency. Concrete line canals reduce seepage losses. Siphon tubes and gate pipes allow more precise water application. Sprinkler systems, though distillery comparatively primitive, begin appear on specialty crop farms.

These technological improvements enable western farmers to cultivate lands antecedent consider overly arid for agriculture, expand the agricultural frontier and intensify production on exist farmland.

Scientific agriculture

The 1920s witness the maturation of scientific agriculture across the west, as research stations, agricultural colleges, and extension services disseminate new knowledge and techniques to farmers.

Agricultural extension services

The smith lever act of 1914 establish the cooperative extension service, but its influence peak during the 1920s. County agents become fixtures in western rural communities, demonstrate new farming methods, organize educational programs, and facilitate technology adoption.

Extension bulletins, demonstration farms, and field days introduce farmers to scientific soil management, pest control, and crop selection. In Idaho solo, extension agents conduct over 1,200 demonstrations yearly by the mid 1920s, reach thousands of farmers with new agricultural knowledge.

Crop improvements

Plant breeding programs develop crop varieties specifically adapt to western grow conditions. Agricultural experiment stations in California, Washington, Colorado, and other western states introduce improved varieties of wheat, alfalfa, potatoes, and fruit crops.

Disease resistant varieties address specific regional challenges. The introduction of federation wheat in the pacific northwest provide resistance to smut disease while maintain high yields. In California, research stations develop nematode resistant stone fruit rootstocks that revolutionize orchard management.

Fertilizers and pest management

Chemical fertilizers become progressively common on western farms during the 1920s, replace or supplement traditional manure applications. Nitrogen fertilizers, in particular, boost yields in irrigated farming systems.

New pest management approaches emerge axerophthol advantageously. Calcium arsenate dust for cotton boll worm control, lead arsenate sprays for fruit tree pests, and fumigation techniques for store grain pests represent significant advances in agricultural chemistry.

Specialization and commercialization

The technological changes of the 1920s facilitate greater agricultural specialization across the west, as regions focus on crops advantageously suit to their climate, soil, and market access.

Regional crop specialization

The western agricultural landscape become progressively specialize:

- California’s central valley intensify production of fruits, vegetables, cotton, and rice

- The Columbia basin focus on wheat, potatoes, and tree fruits

- Arizona expand cotton and winter vegetable production

- Colorado’s front range specialize in sugar beets and feed crops

- The great plains consolidate its position as the nation’s wheat belt

This specialization allow farmers to develop expertise with specific crops and invest in crop specific equipment and infrastructure, increase efficiency and yields.

Vertical integration

Agricultural processing facilities expand throughout the western states during the 1920s. Canneries, pack houses, flour mills, and other processing operations oftentimes locate near production areas, create integrate agricultural economies.

In California’s fruit grow regions, cooperatives build packing and shipping facilities that standardize grading, packing, and marketing. The California fruit growers exchange (sSunkist)exemplify this approach, establish sophisticated marketing networks for citrus products.

Transportation improvements

Expand rail networks and the growth of motor trucking improve market access for western farmers. Refrigerated rail cars allow perishable products to reach distant markets. By 1925, California exclusively ship over 100,000 carloads of fruits and vegetables to eastern markets yearly.

Source: tinnongtuyensinh.com

The development of rural highways and the introduction of motorize trucks give farmers more flexibility in transport products. This transportation revolution connect western agricultural regions to national markets more expeditiously than always ahead.

Social and economic impacts

The technological transformation of western agriculture create profound social and economic changes throughout the region.

Farm size and consolidation

Mechanization encourage farm consolidation, as larger operations could advantageously justify investments in expensive equipment. The average farm size in western states increase steady throughout the 1920s, with especially dramatic growth in the great plains wheat regions.

In Kansas, the average wheat farm grow from roughly 250 acres in 1910 to over 350 acres by 1930. Similar patterns appear across the west, as smaller operators either expand or sell out to larger neighbors.

Labor patterns

Agricultural technology dramatically alters labor requirements. Mechanization reduce the need for year round farm labor while create seasonal labor peaks, peculiarly in specialty crop regions.

This shift contributes to new migration patterns. InCaliforniaa’s agricultural valleys, seasonal labor demands create migrant worker circuits. In greatplains’s wheat regions, custom combine crews follow the harvest northbound each summer, replace the threshing crews of earlier eras.

Rural communities

Western rural communities experience significant changes as agriculture mechanize. Farm population densities decline in many regions as larger, mechanized farms require fewer operators. Small towns serve as agricultural service centers either adapt to new economic patterns or decline.

The automobile revolutionize rural social life, expand the geographic range of community interactions. Farm families could travel to larger towns for shopping, entertainment, and services, reduce their dependence on the smallest rural communities.

Environmental consequences

The agricultural transformation of the 1920s create significant environmental changes across the western landscape.

Land use changes

Mechanization and irrigation enable cultivation of lands antecedent consider unsuitable for farming. Across the great plains, tractors and combine facilitate the conversion of millions of acres of native grassland to wheat production.

In California’s central valley, irrigation transform arid lands into intensively cultivate cropland. The acreage under irrigation in California increase from roughly 4.2 million acres in 1919 to 5.7 million by 1929.

Soil challenge

Intensive cultivation create new soil management challenges. The heavy plowing enable by tractors increase erosion risks in many regions. Irrigation without adequate drainage lead to salinization problems in parts of California, Arizona, and Utah.

These environmental challenges remain mostly unaddressed during the prosperous 1920s but would emerge as critical issues during the drought and depression of the 1930s.

Agricultural prosperity and instability

The technological transformation of western agriculture occur against a backdrop of economic volatility that shape adoption patterns and outcomes.

Post-war boom and bust

The immediate post-war period (1919 1920 )see high agricultural prices that encourage expansion and investment. Western farmers purchase equipment, land, and infrastructure, oftentimes finance these investments with borrow capital.

The agricultural depression that begin in 1921 create financial stress for many farmers who had invested in new technologies. Commodity prices fall sharp while debt obligations remain. In wheat grow regions, prices drop from ove$2 2 per bushel in 1919 to less than$11 by 1922.

Adaptation and survival

Western farmers respond to economic pressures with increase efficiency. Those who successfully integrate new technologies oftentimes weather the economic challenges more efficaciously than those who maintain traditional methods.

Specialization, cooperative marketing, and value add processing help some western agricultural regions maintain profitability despite decline commodity prices. California’s fruit industry, Washington’s apple growers, and Idaho’s potato producers develop marketing strategies that partly insulate them from commodity price fluctuations.

Legacy of the 1920s agricultural transformation

The agricultural revolution of the 1920s establish patterns that would define western farming for decades to follow.

Mechanization, irrigation, and scientific agriculture become the foundations of western agricultural production systems. The specialization patterns establish during this period — California’s fruit and vegetable industry, the Columbia basin’s wheat production, the great plains wheat belt — persist in modify forms today.

The tensions create during this period — between efficiency and equity, between productivity and sustainability, between technological optimism and environmental limits — continue to shape agricultural debates in the American west.

The 1920s represent not plainly a technological transformation but a comprehensive remaking of western agricultural landscapes, communities, and economies. This agricultural revolution establish the foundations for modern production systems while create challenges that would emerge more full in subsequent decades.

MORE FROM ittutoria.net